Case Study- Dr. Esha

Introduction:

Lower back pain(LBP) due to myofascial tightness

Lumbar dysfunction is a serious health issue affecting 80% of people at some time in their life time. It has been considered as one of the important cause of disability. Myofascial abnormalities may lead to connective tissue fibrosis, increased tissue stiffness and further movement impairment which may contribute to LBP chronically.

Therapeutic approaches used to manage low back pain include: nonprescription analgesics; prescribed pharmaceuticals; electrical modalities; acupuncture; shoe lifts; low back corsets and back belts; patient education and; manual procedures including soft tissue therapy, mobilizations, and spinal manipulative therapy.

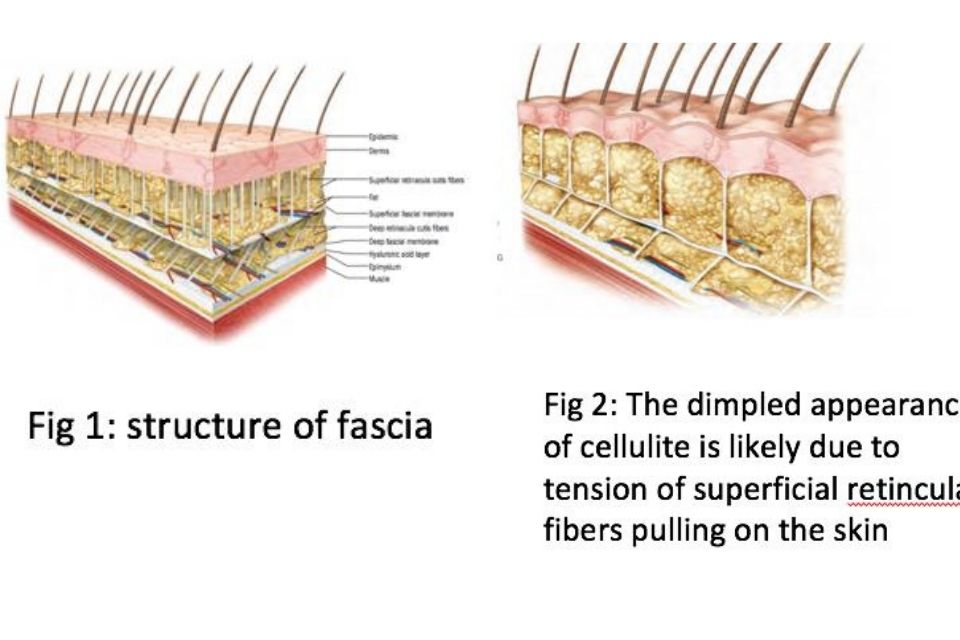

Structure of fascia:

Fascia is composed of three layers: an outer superficial layer, a middle layer, and a deep inner layer. Fascia is a connective tissue that encases and connects all muscles and organs in the body, providing lubrication and support. There is continuity in this fascial envelope from head to toe. It has been likened to yarn in a sweater or a spider’s web. Anatomical displays tend to show the bones, muscles, nerves and veins, but leave out the fascia that connects them. If left intact this would allow people to see the full picture, shedding light on these fascial connections. Fascia is made up of layers of collagen.

It surrounds and holds together all parts of the body. It allows for movement and connectivity between parts of the body and plays a big part in ensuring our structural health and range of motion. The collagen is laid down in specific directions in response to stress exerted on the tissue. It is a living tissue containing fluids and blood vessels. Fascial fibres run in many directions, allowing it to move with the surrounding tissues. Its structure changes based on a person’s movement patterns and in response to stressors. If there are restrictions in the fascia, the muscles and joints are unable to move freely. If an individual develops bad posture, the fascia molds accordingly causing the body to become stuck in a maladaptive position. These compressions and misalignments can even lead to inflammation and joint deterioration if prolonged.

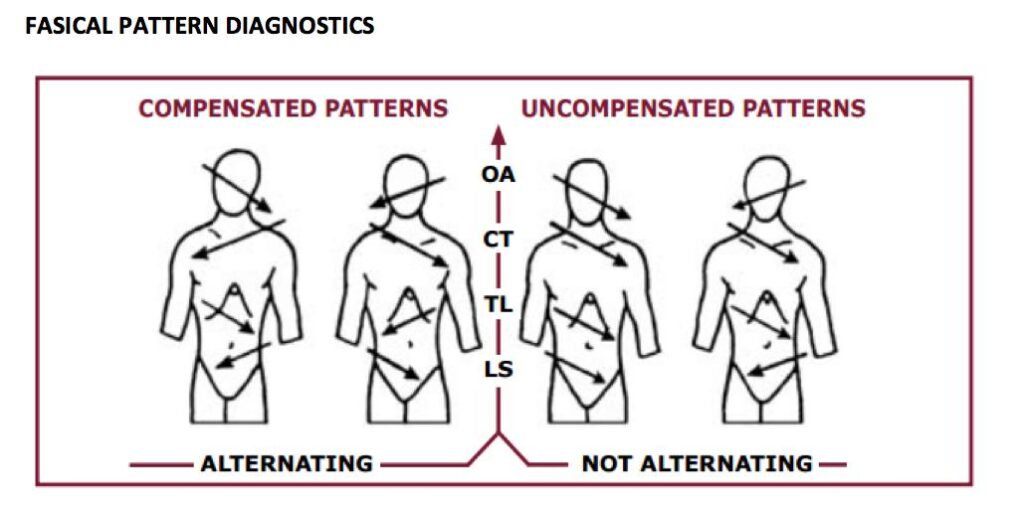

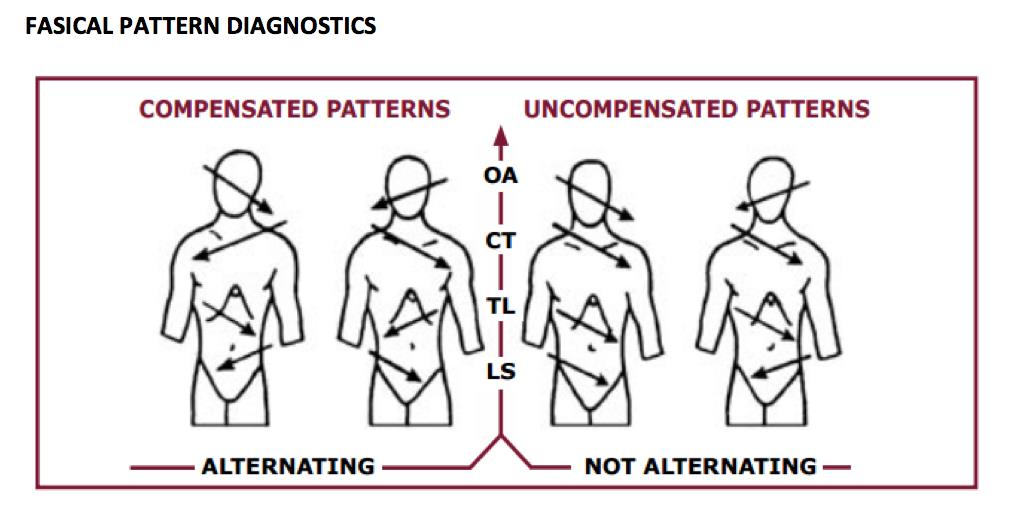

The ideal pattern is demonstrated by equal fascial glide in the side to side and longitudinal directions. Thus, there would be no apparent preference for fascial rotation or sidebending to either the right or the left, in any transitional zone. This ideal pattern is seldom if ever seen in the clinical setting. Alternating patterns of fascial ease and restriction are common. Usually a rotational bias in one transition zone is accompanied by an opposite fascial rotation in the next zone throughout the body. This alternating pattern, found in healthy subjects, was considered compensated (Fig below). Zink reasoned that counterbalanced.

Tissue Texture Abnormalities

- Palpable change in tissues from skin to peri-articular structures

- Represents any combination of vasodialation, edema, hypertonicity, contracture, fibrosis & itching, pain, tenderness, parasthesia

Types of changes include the following:

- bogginess, thickening, stringiness, ropiness, firmness, increased/decreased tempurature, increased/decreased moisture .

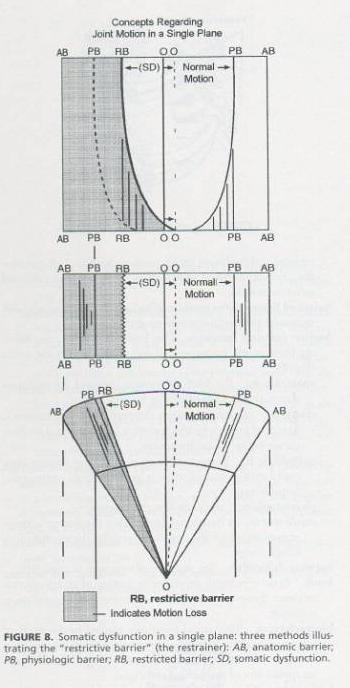

Barrier Types

In testing for restriction in motion, in theory, we are “engaging barriers,” which is to say, we are testing how far a joint/limb/vertebral segment/whatever is “willing to go,” and we are comparing that to the other side, or to what is considered a normal range of motion.

- Physiologic barrier: a point at which a patient can actively move a given joint

- Anatomic barrier: a point at which a physician can passively move any given joint p

- Pathologic/restrictive barrier: a point at which resistance is felt or range of motion is limited (i.e. before reaching the physiologic barrier).

The Concept of Barriers

Description of Myofascial Release:

Myofascial release (MFR) reduces tension by applying gentle sustained pressure to fascial connective tissue. The slow gentle pressure reduces pain and increases mobility. Myofascial release is used to treat musculoskeletal pain and loss of mobility. It is a holistic treatment that treats the body as an integrated whole. Myofascial therapy allows muscles and connective tissue to release restrictions and improve overall functioning. MFR is achieved through releasing tension at trigger points by applying a gentle and constant pressure over the tissue until the tissue is released. This is done in layers, increasing pressure as the fascia releases. Pulsing, vibration, heat, or even spasm may be felt as the fascia is released. After the client will feel a sense of relaxation and a reduction in pain.

Diagnostic technique (Global listening technique)

Gathering information from the entire body in a way that allows the practioner to accurately determine the general location of greatest tension in the person at the time of evaluation.

Importance of Fascia in Osteopathy:

Fascia is extremely important to osteopathic diagnoses and treatment. This connective tissue allows the manual practitioner to view and treat the client in a holistic manner. When an individual experiences injury or inflammation, the fascia loses its freedom of movement. This creates tension and tightness in the body. When muscles contract and joints lose their mobility, it increases tension in the surrounding fascia. In order to return the body to homeostasis, tension needs to be released and mobility returned to the joints, muscles, and fascia. A fascial restriction in one part of the body creates tightness and a reduced range of motion in other areas as well. When fascia is released overall functioning is improved. Osteopathy includes three major components:

mobilizations, muscle energy techniques, and soft tissue therapy. Trigger point therapy and myofascial release fall under soft tissue treatment. Mobilizations help to release and mobilize the joints, while fascial release helps to ease tension in the muscles and surrounding tissues. Including myofascial release in therapy allows for a more global and integrated treatment for the patient.

Report of case:

A 30 years old female having pain in lower back for 4 years, was taking all possible conventional treatment but never recovered permanently.

Examination:

History of patient:

- Location of pain: lumbo-sacral area (right side)

- Duration of pain : since 4 years

- Mechanism of injury: work related

- Aggrevating factors:

- Prolonged sitting

- Prolonged standing

- Walking more than 15 mins

On observation:

Overall posture:

- Body symmetry: primary concavity at l3-l4 towards the right side

- Lateral bending: towards the left side

- Sloppiness:

- Right shoulder high

- Right elbow medially rotated

- Right iliac crest high and anterior

Osteopathic assessment:

Tenderness: on palpation, right Quadratus lumborum was tender

VAS score: 7

0 ————- 10

X-RAY findings:

Strain Counter-Strain Technique

Treatment positions for strain counter strain technique22: The patient is prone with the trunk laterally flexed toward the tender point side. The therapist stands on the side of the tender point and places his/ her knee on the table then rests the patient’s affected leg on his/her thigh. The patient’s hip is then extended and abducted, and slightly rotated to fine-tune, this position was maintained for 90 sec. Post this the subject is passively placed in a relaxed position.

Procedure:

Outcome measurements:

- Pain (VAS score)

- Body symmetry (Global listening test)

Myofascial release for quadratus lumborum:

QL muscle group plays a prominent role in normal body mechanics. This muscle group is composed of several small muscles that are located deep within the muscle mass of the lower back. The anatomists have accorded the role of coastal and vertebral attachments in the process of respiration and moving of lumbar spine respectively. QL probably helps to extend lumbar spine, causes lateral flexion and 12, 13 is also an important stabilizer of lumbar spine.

Quadratus lumborum can be palpated at the tender point screening along the belly of the muscle between the 12th rib and the iliac crest.

- Land on the surface of the body with the appropriate “tool” (e.g., knuckles, or forearm).

- Sink into the soft tissue.

- Contact the first barrier/restricted layer.

- Put in a “line of tension.”

- Engage the fascia by taking up the slack in the tissue.

- Finally, move or drag the fascia across the surface while staying in touch with the underlying layers.

- Exit gracefully.